Today’s Interview with an Author is with Dr Dave Lunt, evolutionary geneticist at the University of Hull, UK. His lab uses phylogenetic and bioinformatic approaches to better understand genomes, evolutionary processes, and biodiversity. He recently published his work ‘The complex hybrid origins of the root knot nematodes revealed through comparative genomics’ with us, and we were very interested in hearing more about the impactful research and his experience publishing with us.

PJ: Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I’m an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Hull in the UK. I’m investigating “what’s in a genome and why” i.e. what forces shape the content and diversity of eukaryotic genomes. I use primarily phylogenetic and bioinformatics approaches and have a particular fondness for under-studied phyla. Additionally I’m very interested in the rapid developments in reproducible research, open science, and open access publishing.

PJ: Can you briefly explain the research you published in PeerJ?

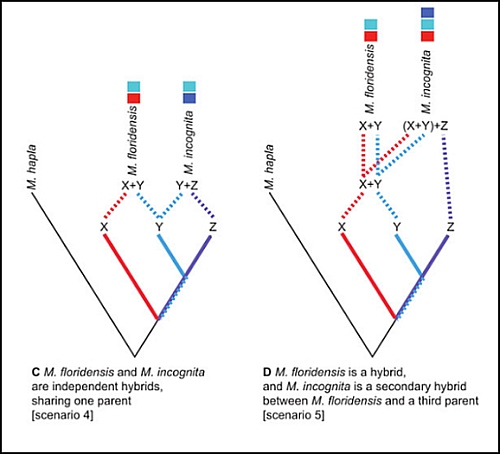

The root knot nematodes have fascinating biology, exhibiting a diverse range of reproductive modes even between closely related species in the same genus. Additionally they are major global agricultural pests, parasitizing almost all human crop species. We set out to understand the origins and genomic diversity of one of the major pathogen species, Meloidogyne incognita, by testing the hypothesis that this asexual parthenogen originated from an interspecific hybridization between two other species. Our comparative genomics revealed that yes, it was an interspecific hybrid and that one of the parental species was the sexual species M. floridensis. Surprisingly however the genome sequences revealed that M. floridensis was itself an interspecific hybrid, and so M. incognita was a complex double-hybrid species. This fascinating set of nested hybrid origins is further evidence that hybridization in animals may be generally more common and important that has been recognized previously. The hybrid genome structures detected here also suggest mechanisms by which the enormous host range of these parasites may have evolved.

PJ: Why do you think this work is significant in your field of research?

Although the situation is changing with the rise of genomics, the study of animal speciation is only just discovering the importance of hybridization. This has been well appreciated for a long time by botanists, but its importance to animals has long been largely dismissed. The double-hybridization we discovered highlights strongly that these events have been important in species formation and adaptation. I think it’s also very important to ‘know your enemy’ and we are gaining important fundamental knowledge, with real applied consequences, about these devastating crop pathogens.

PJ: What surprised you the most with these results?

Two things really: Firstly, that the parent of the hybrid species was itself a hybrid was totally unexpected. This makes the situation both much more complex and much more interesting. Secondly, although I really shouldn’t be by now, I am still always surprised how beautifully powerful comparative genomics is to reveal complex evolutionary histories.

PJ: Which figure in the manuscript do you think best summarizes your results?

Figure 2 (extract below) best summarizes the whole study, outlining a range of possible hybridizations. I was skeptical for a long time that it was the last and most complex double-hybrid event. Now it reminds me of Carl Sagan’s quote: ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence’, I guess that’s exactly the sort of evidence genomics gives us now as a routine matter.

PJ: Why did you choose to reproduce the complete peer-review history of your article?

Well why not? We had excellent reviewers who highlighted some aspects a reader could also find interesting.

PJ: What kinds of lessons do you hope the public takes away from the research?

I would like the public to know that fundamental ‘discovery science’ biological research (like evolutionary genetics, investigation of reproductive systems, and phylogenomics) builds the foundations for important applied outcomes. Our evolutionary genomics research, even if it were not of really major agricultural pests, would still be a great contribution and is one small example among very many.

PJ: Where do you hope to go from here?

This was the first genome from a much bigger study to examine the effects of reproductive mode on genome content and diversity. We are asking how the loss of meiosis, parthenogenetic reproduction, or inbreeding, influences genome size, the spread of transposable elements, or divergence of gene families? Next, we have a lot more comparative genomics analysis to do on many more nematode genomes.

PJ: How did you first hear about PeerJ, and what persuaded you to submit to us?

I’ve known about PeerJ since its launch and we submitted because of the open access model and modern approach to publishing. Glowing recommendations from colleagues also helped.

PJ: How would you describe your experience of our submission/review process?

Submission and review were very efficient, rigorous and professionally done.

PJ: Did you get any comments from your colleagues about your publication with PeerJ?

Positive comments only! There are a group of evolutionary biologists at the University of Hull who are all keen on modern open access journals. PeerJ fitted very well with this.

PJ: Would you submit again, and would you recommend that your colleagues submit?

Definitely

PJ: In conclusion, how would you describe PeerJ in three words?

Rigorous, fast, beautiful

PJ: Many thanks for your time!

The University of Hull fund Publication Plans for their faculty (meaning that authors from their institutions will have their publication plans automatically paid using funds made available via the library). Check if your Institution has a Publishing Plan with us and submit your next article to PeerJ. You’ll be joining thousands of satisfied authors!